Reflections on Critical Mixed Race Studies conference

Posted on

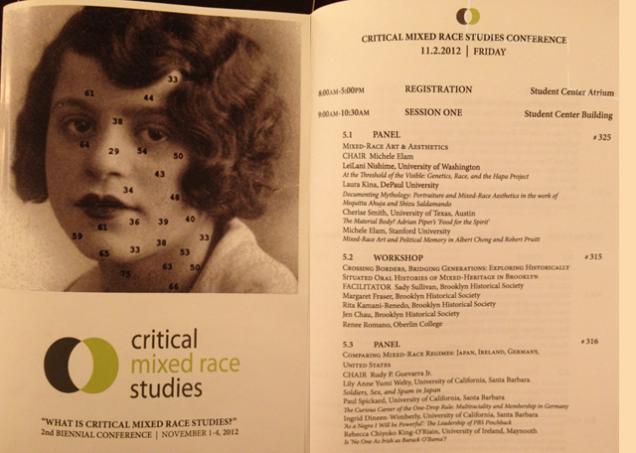

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to attend the second biennial Critical Mixed Race Studies Conference at DePaul University in Chicago. I was excited to return after having attended the inaugural conference in 2010. This time, I went as a representative of Crossing Borders, Bridging Generations to share with conference participants the work around identity, multiraciality and oral history that the Brooklyn Historical Society has been doing and explore some of the powerful implications CBBG can have both inside and beyond the walls of academia.

To give you a little background, the Critical Mixed Race Studies (CMRS) Conference is organized by faculty members of various universities and hosted by DePaul University’s Global Asian Studies and Latin American and Latino Studies programs. Though mixed race studies has existed for some time, the conference—and a forthcoming academic journal—were created to provide a space for “a recursive and reflexive approach to the field.” According to conference organizers, CMRS is “the transracial, transdisciplinary, and transnational critical analysis of the institutionalization of social, cultural, and political orders based on dominant conceptions of race. CMRS emphasizes the mutability of race and the porosity of racial boundaries in order to critique processes of racialization and social stratification based on race. CMRS addresses local and global systemic injustices rooted in systems of racialization.” With this in mind, I went to the conference eager to engage in conversations about the changing discourse around race and racial identity, race-based social stratification that persists in our society, and the role of scholarship, activism and the arts in challenging dominant narratives around mixed-race.

When I arrived to DePaul on Friday, the conference was bustling and the sessions were packed. Panels, workshops and roundtables brought together scholars from a variety of disciplines, students, artists, and activists to discuss topics that included: media representations of mixed-race subjects, racial mixing and mestizaje in the Americas, mixed-race identity formation in schools, literary representations of mixed race, racial passing, and counseling for mixed-race populations. One highlight included a roundtable on the U.S. Census titled “Changing the Latino Question or Gunnin’ for the Census Again.” One of the participants in our roundtable discussion was Eric Hamako, a long-time scholar of mixed-race studies. Eric was nominated by a coalition of mixed-race community organizations to serve on the U.S. Census Bureau’s National Advisory Committee (NAC) on Racial, Ethnic, and Other Populations. Eric came to the roundtable to hear what folks had to say about “the Latino question” and explore the benefits and complexities of having a separate Latino/Hispanic question rather than including Latino/Hispanic as a racial/ethnic category along with Black, Native American, White and Asian. Throughout the conference, he listened to what members of the mixed race scholarly community had to say about the Census. You can read more about Eric’s questions and thoughts here.

Another highlight included the addition of “Mixed Roots Midwest,” a collaboration between the Mixed Roots Film and Literary Festival and the CMRS Conference to bring short films, a filmmakers panel and a live show to the conference. The festival offered a different kind of space to engage in conversations about narratives of mixed experiences in film, as well as how mixed filmmakers have explored these themes in their work.

I was also pleased to see quite a few geographically-specific panels, such as “Historical Mixed-Race Populations of the Carolinas, Virginia and Appalachia,” “Hafu: Historical and Media Representations of Mixed-Race in Japan,” and “Mongrel Nation? The Future of Critical Canadian Mixed-Race Theory.” Much can be gained by bringing together different perspectives on questions around mixed-race that are centered over a particular geographic and historical location. Dialogue that engages diverse angles and lived experiences in relationship to particular places, spaces and moments in history can be rich and insightful and can lead to new questions around how communities move forward. This is what we hoped to accomplish at our workshop, “Crossing Borders, Bridging Generations: Exploring Historically Situated Oral Histories of Mixed-Heritage in Brooklyn.” It was a shame that Hurricane Sandy kept Sady Sullivan and Jen Chau from being at the conference, but we were fortunate to have Ken Tanabe join Renee Romano and myself to share a little bit about how CBBG and Loving Day have opened up new spaces to explore these questions in vibrant, bustling, and ever-changing New York.

After sharing some basic information about CBBG and giving participants a quick tour of our CBBG website, Renee and I discussed how CBBG can be an important resource and tool both within and outside of academia. Renee recounted her own experience as a doctoral student seeking to research Black-White marriages in postwar America and running into numerous challenges as her advisors warned her she would not find any records or primary documents. Renee was particularly excited for the development of a rigorous and expansive oral history archive around mixed-heritage and identity that students and scholars can use in the future and that could be accessed from anywhere. I discussed the importance of creating spaces in which to explore these topics within community settings and expanding beyond the walls of academia to involve voices that are often excluded. Both Renee and I also discussed the importance of placing the voices of mixed families and individuals at the center—rarely does research about mixed people allow us to tell our stories on our own terms. We are too often spoken about, using tropes and representations that are stigmatizing, misrepresentative, stereotypical, or superficial.

Since its launch at What are You? Mixed Heritage in Brooklyn in 2011, CBBG has held 15 public programs in New York City, reaching an audience of over 700 people. We have collaborated with community institutions such as El Museo del Barrio, Loving Day, the Museum of Chinese in America, and the Brooklyn Museum. We are expanding the spaces where people begin to think about issues of mixed identity, or where people continue to broaden and deepen their understanding of how race continues to shape society and our lives.

During our workshop’s Q&A, we received a comment that pushed me to consider how CBBG can fit into the larger field of CMRS and can continue to push forward critical dialogues around mixed-race. A participant who now lives and teaches in Milwaukee fondly recalled her time in New York and felt that conversations about race and mixed-race in extremely segregated Milwaukee could not necessarily happen at the same level as they might in a place like New York. I was left wondering if this was true. New York is by no means some sort of racial utopia. In my presentation I mentioned the NYPD’s Stop-and-Frisk policy that disproportionately affects young Black and Latino men, aggressive processes of gentrification, and the enduring wounds and scars of events like the Crown Heights riots, 9/11, and more. Even some critical analysis of Hurricane Sandy’s impact sheds light on the disparities and distances that exist among New Yorkers. Yet, there is something about New York’s geography, transportation system, immigrant history and transience that allows people (or even forces us?) to come together in unique ways and challenge each other in sometimes productive –often times not—ways. This is not to say that other communities, other parts of this country, cannot engage in critical conversations about racial justice. Rather, those conversations must be built in spaces that take into account the unique histories of those cities, towns, or regions. A conversation about immigration will look and sound very different in a city that has only recently began to take in new immigrant populations, but their conversations around Black-White families post-Civil Rights may be far deeper and far more personal than they could be elsewhere.

What was beautiful about the participant’s comment was that it led to a conversation about how a project similar to CBBG could provide an entryway into sparking the dialogue she hopes to see in her city. If the conversations aren’t happening on a community level, then something like a public program—a film screening, speaker panel, or artistic event—could be the perfect spark for important and critical dialogues. An oral history project is a project that a professor could assign to her students in order to encourage them to truly listen to the lived histories around them and to challenge the preconceived notions they may have of their neighbors. Critical conversations about mixed race have, for too long, either been limited to exclusive spaces that only a certain class of people can participate in or, been limited to pop culture’s superficial forays into multiculturalism. CBBG can begin to bridge this divide, while at the same time providing an invaluable resource and tool to those conducting scholarly research—many of whom were at the conference—or trying to engage communities in these important, and sometimes difficult, dialogues.