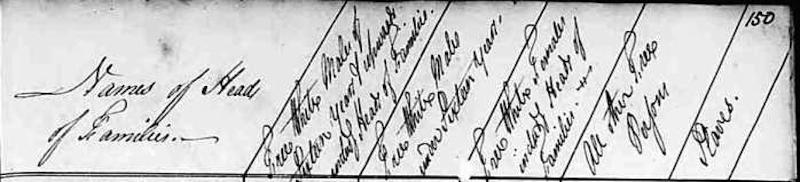

Whether or not race can be said to have originated in many societies or just one, there is no doubt that it was a flourishing concept in the West when the United States was founded. As a result, the U.S. has always existed in a world where belief in racial difference has also existed; it doesn’t have any roots in Antiquity or the Middle Ages, when people relied on other types of difference (e.g. religious) to make distinctions between various groups. It is not surprising then that race has been central to Americans’ thinking about social hierarchies. An even greater foundation for race thinking in the U.S., however, was likely its paradoxical status as a slave state devoted to the principle of liberty. As in other European colonies and former colonies, race had long been used in North America to justify extermination, conquest and enslavement of non-European peoples. Accordingly, the United States’ founding documents enshrined the political and social importance of race in the new republic. The Constitution mandated that slaves be treated as equivalent to 3/5ths a citizen when counting the population, and consequently, the very first U.S. census in 1790 classified people as free white males, free white females, other free people, and slaves. At the same time, the nation’s first immigration (and naturalization) law established that only white immigrants could be granted citizenship.

The inclusion of racial categories on the very first U.S. census began a tradition that is still with us today. Every decennial census ever fielded in the United States has included a question on race. However, the categories themselves have varied markedly over time, and may very well be changed yet again for the 2020 census. As mentioned above, “white” was the first racial category to be explicitly included on the census, followed by “Indians” in 1800, and “Colored Persons” in 1820. These categories—white, red, and black—can be considered the foundational races in the United States, or the basic groupings with which the first Americans tried to classify the people around them. And each of these groups was assigned a particular place in American society. Only whiteness conferred full citizenship rights; Blacks and Indians were not second-class citizens so much as they were simply not considered citizens at all, although for different reasons. Ironically, despite having been the original inhabitants of North America, Indians were simply considered foreigners, outsiders to the nation, and members of other sovereign nations (i.e. tribes). Treating blacks as foreigners was a trickier business. For one thing, the Middle Passage virtually eradicated their ties—political, cultural, and other—to Africa. For another, blacks could not be expelled beyond the boundaries of the United States—as American Indians were—because such a move would have meant giving up the slave labor that was so central to the American economy.

This early politico-economic configuration grew more complex with time, as the United States’ territory and population expanded, and along with these changes came an increasing number of census racial categories. An Asian race (“Chinese”) was first introduced on the 1870 census, and with the addition of categories such as “Japanese” in 1890, “Filipino” and “Hindu” in 1920, and “Korean” in 1930, Asian categories have come to represent the largest number of checkboxes on the U.S. census race question today. The proliferation of nation- or ethnicity-based categories for Asians only—when in contrast there has always been only a single category each for “Whites” and “Blacks”—reflects the historical conditions in which people migrated to the U.S. from Asia. The earliest waves of these migrants not only arrived in distinct time periods—first Chinese, then Japanese, and so forth—but they were routinely pitted against each other as workers, in order to keep them a divided labor force that could not organize to press for higher pay or better working conditions. The idea then of a pan-Asian community has developed relatively slowly in the United States, and was hardly in place when the census first tried to enumerate people of Asian descent.

IMAGE: United States Census form 1790 via Racebox.org