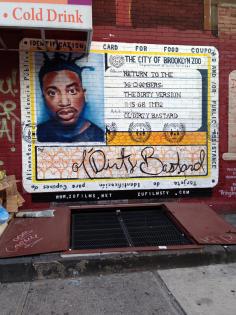

I am newly 30. A new Brooklynite. It is the third week of May, so the early afternoon sun is a vibrant yellow and comfortably warm. My hair, recently blow-dried straight by the Dominican ladies on Putnam Avenue, bounces and moves with the wind just how I like it to. I am wearing short shorts, a beige blouse with a ruffled collar and a lightweight lavender cardigan. Tall, lovely Brenda and I meet between our two brownstones, giddily compliment each other’s outfits and hair, and walk down Franklin Avenue, bypassing bodegas, the West African video rental spot, the Bed Stuy library and the huge mural of Old Dirty Bastard. Brenda is a model and actress and I work in advertising. We are trying a new place for brunch.

Bush Baby is on Fulton Street near Bedford Avenue. Nearly everyone is black on these blocks, but there are different ways to be black: grand white bubou wearing holy man black; teenaged, baggy jean, fitted cap black; gray haired lady in nurse’s white church dress and panty-hose black; mine and Brenda’s way, and so many more.

Less than six tables fill the small restaurant because of the large bar towards the back. The lighting is dim and amber hued even though it is daytime. Live orchids adorn the tables and the walls are exposed brick. There is music, I think Femi Kuti, playing over speakers. A sweaty and overweight waiter nods our way as he busily attends to a table of two men chatting in trendily tattered skinny jeans. “Sit anywhere,” he says.

Brenda has just started online dating after a cruel and messy breakup with a Dominican bus boy. He cheated on her with nearly six different women over the course of three months. She’d known about some of the flings, but kept going back to him until one day the humiliation became too much. She tells me that she is excited to meet the new man she has been emailing. I tell her that I am on again with Drew. Just the night before, we have booked a trip to the Bahamas to work on our problems. A former collegiate basketball player, he is tall, fit, has an infectious smile. His manner is kind and gentle; his family is appropriate. But he does not read or like me to wear my hair curly and he hates that I burn Nag Champa and play Alice Coltrane in my apartment more than Jay Z. I don’t leave him, though. I don’t want to be alone like my mother.

Between laughs and sips, Brenda and I order cocktails and consider the menu. There are traditional, vegetarian and vegan soul food dishes. A robust selection of black, green and white teas. The waiter comes to us, sweating still. We order salmon croquettes and croissants.

The restaurant door opens and a tall, fortyish bald man walks in with luminous brown skin and a full beard with gray sprinkled throughout it. He wears a navy sweatshirt and white hued khakis rolled up around his ankles. His brow is very square, his eyes are black and piercing, and for quite some time, they don’t leave mine. He seats himself at the table closest to us, in the chair next to me. His socks are funny: neon green with navy and pink stripes.

Brenda and I continue our conversation, and without an invitation, the man in the white pants joins it, asking us our names. Another fortyish man walks in and sits across from the man in white pants, and somehow, we are all soon discussing the problems that black men and women have with relating.

“Black women are ‘together’ professionally, but most are too emotionally immature to sustain a healthy relationship with a man. They have no idea how please him,” says the man in white pants.

I am just as overpowered by the audaciousness of his sexist opinion as I am his physical beauty. Thinking of my mother and my sister whose daughter’s father is chronically unemployed and missing in action, I respond. “Are you serious? Black women may be ‘together’ but we are surrounded by men who aren’t and deal with them anyway, often to our detriment.”

“You think the pool of eligible black women is so large?” the man in white pants asks. “I am vegan and very spiritual. The woman for me does yoga, eats healthy, she’s spiritually fluid. It isn’t easy to find.”

“You never know what kind of person might be right for you until you find her. Standards are important, but I don’t know if detailed lists about what a person needs to eat and how she works out and how she thinks about God are necessarily the answer to finding love.” I am trying to make a case for solidarity.

The friend interjects. “Well, the point is that black women are more of a mess than you guys like to believe about yourselves.”

Tempers flare, but, eventually, I retreat, realizing that this argument is unwinnable. You don’t fight these battles over brunch and, to me, we are not on opposing sides of anything. The guy in the white pants and I begin a side conversation.

“So do you prefer black men?”

“I do,” I say, to my own surprise. This is not entirely true. I just prefer men. My childhood boyfriends were all white, my coworker crush from two years before was Korean.

“I like your socks.”

He says thank you. Something happens to his face, maybe it relaxes, or contracts slightly. It changes. His fingers are very lean.

Brenda and the other guy continue arguing, and I occasionally dip into their conversation to defend her. The man with the white pants and I talk about Paulo Coelho and Manning Marable’s new book on Malcolm X. There are smiles and long glances that I eagerly return. Uncharacteristically, I am not coy. It feels like spring on my skin to share this space with this stranger. My face flushes, my shoulders burn. I am aware that I have found an opening and arrived at a precipice. Everything about me is different.

When it is time, Brenda and I pay our bill. I walk to the ladies’ room to reapply lipstick, fluff out my hair. The man with the white pants – his black eyes follow me until I return. Warm with adrenaline and anticipation, I linger a bit before offering a tentative goodbye. Brenda and I leave to wander back down Franklin Avenue, past the mural, bodegas, and video stores once more.