People navigate living between racial categories in complicated ways. Their identities are formed through equally complicated intersections of experience, family history, politics, geography and context. My narrators repeatedly told me about the painful experiences of being interrogated about “what” they were, of not feeling like they fit in with either side of your family, of feeling “unsupported” and illegitimate in whatever heritage or identity categories they assumed. Often I found myself carrying a story with me long after an interview was over, turning it over in my head, relating it to an experience I had had that was similar.

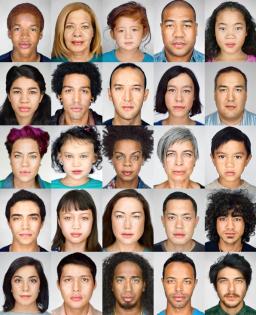

Mixed-heritage, mixed-race people are told that we are the “changing face of America,” as one National Geographic article in 2013 put it. Strangers on the street sometimes tell us this too, smiling and nodding as if this were somehow inherently desirable. We are simultaneously made to feel as though we are outsiders and potentially dangerous and simultaneously somehow “cool” and held up as “the future”: an example of how tolerant, post-racial, and multi-cultural our society allegedly is. Less often talked about in popular culture is how static racial categories are, or their role in a structurally violent system in which people who are in-between are perennially forced to justify themselves and their identity. What are you? Where do you fit in? Are you a threat?

Race does still matter in the United States, both structurally and in our day-to-day interactions. Whites on average have twice the income and as much as six times the amount of wealth as blacks, and black men are twice as likely as white men to be unemployed. There is evidence of racial bias in our education system, our health care system, incarceration rates, and employment levels.

In a system like this, being racially ambiguous can define not only the way people think of you, but also what sort of access to resources and privileges one might have. People told stories of looking darker or lighter than the rest of their family members, and this structuring how their cultural heritage or racial identity was viewed from the outside as well as how they were treated or expected to act. Many people grappled with the ways that “looking white,” even if they did not identify as so, meant that they had access to sets of privileges that other members of their family might not have.

One of the most salient lessons I learned participating in this project is that oral history is vital to pushing the conversation about race, heritage, identity, and experience. Through storytelling, we learn about each other and ourselves and we create the space to have difficult conversations about such issues. Oral history allows for multiplicity: for the varied, nuanced, and complicated stories of identity to be told - not flattened to static racial categories.

In allowing for multiplicity through oral history, the Crossing Borders, Bridging Generations project provided an essential space for ambiguity, a space for people’s lived experiences to be taken seriously, valued, and allowed to be the difficult, winding things they are. What can creating the space for such oral histories do in the world? I do not want to be so naive as to think that we can, through storytelling, deeply change the racist structures that we exist in, but I do know after conducting many of these interviews, that we can, at least, make an impact on the way that they are told, remembered, and understood.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: Martin Schoeller for "The Changing Face of America," National Geographic, 2013