Few others agreed with Arendt in 1954 that attacks on miscegenation laws should come before the fight against segregation in public accommodations or restrictions on voting rights. The U.S. Supreme Court, already worried about resistance to its ruling in Brown, declined to even hear two mid-1950s cases about the validity of intermarriage laws. But on the state level, changes were brewing. In 1948, the California Supreme Court invalidated that state’s miscegenation law on the grounds that the state could not prove that barring marriages between people of different races harmed the larger social good, marking the first time in the 20th century that a court declared a miscegenation law unconstitutional. As segregation came under increased public criticism, many of the twenty-nine states that still barred intermarriage, especially those in the West, moved to repeal their laws. The fact that only sixteen states still had such laws on their books at the time of the Loving decision reflects this slow incremental retreat from the prohibition of interracial marriage.

Southern states, however, had little interest in voluntarily repealing their laws prohibiting interracial marriage and southern state courts repeatedly upheld such laws as constitutional in the years before Loving. But by the mid-1960s, the Supreme Court had begun to reconsider its ruling in Pace, which had allowed states to prohibit interracial sex as long as both the black and white offenders were punished equally.

By 1964, Congress had passed a civil rights law that forbade discrimination in employment and public accommodations, and the Supreme Court had ruled against nearly all forms of segregation—except those related to sex and marriage. When the court faced a Florida case in 1964 that directly raised the question of the constitutionality of laws that made interracial sex a crime, it overturned its precedent in Pace, calling that ruling a “limited view of the Equal Protection Clause which has not withstood analysis in the subsequent decisions of this court.” With McLaughlin v. Florida, the Supreme Court invalidated laws that punished interracial sex. That ruling, however, did not extend to laws that barred interracial marriage. It would require another Supreme Court decision to overturn the remaining miscegenation laws.

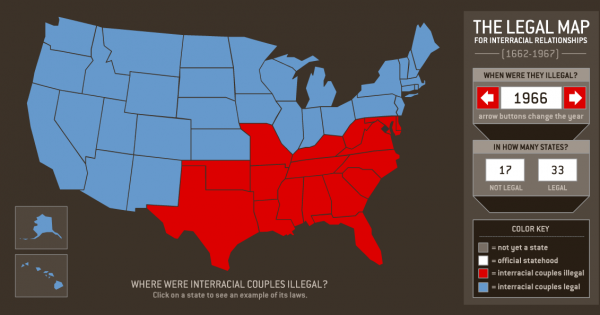

IMAGE: Map showing states where interracial marriage was still banned in 1966. This is an interactive map which shows the changing landscape of interracial marriage legality in the U.S. from 1662 - 1967: Loving Day - Legal Map.